The following is an essay that brings together all my thinking about my philosophy of teaching. This is the considered, researched, position of why I do what I do. This is a work in progress as the second and third areas of investigation need a lot more work – I have decided to put it aside to write a much short, less formal piece as advised by trusted colleagues. Appreciate feedback 🙂

My teaching philosophy is founded on an “image of the child.” Loris Malaguzzi advocated for the importance of an educator’s “image of the child.” “This theory within you,” he claimed, “pushes you to behave in certain ways; it orients you as you talk to the child, listen to the child, observe the child. It is very difficult for you to act contrary to this internal image…” (Malaguzzi 1994:1). My teaching philosophy is founded on an image of the child as active, capable, and curious. The child is an individual human being, not an abstract concept, that must be seen “in relation to other children, teachers, parents, his/her own history, and the societal and cultural surroundings.” (Rinaldi 1998:113) This shapes my expectations and interactions which can be expanded upon within three main areas; the mental learning space, a three-dimensional curriculum, and the physical space.

THE MENTAL LEARNING SPACE

Ken Robinson states that “education should enable young people to engage with the world within them as well as the world around them” (Robinson 2015:45). I believe a culture of mindfulness teaches how to engage with the world within. Consequently, students are ready to engage with the world around them, including a healthy classroom community based on high-trust.

A culture of mindfulness is not simply journalling time and meditation sessions though these can be useful. It is a focus on the present moment, an awareness of how feelings affect behaviour, and how the human brain can be reprogrammed not to react but reflect and then act. Within this culture, students are better able to cope with the world around them because the world within has the tools to be balanced and secure. Furthermore, with these tools, they are able to function within and contribute to, a healthy classroom community. Together with a culture of mindfulness, the foundation of a healthy classroom community is trust.

Whenever I start the new year I begin by discussing classroom culture and asking student’s what they want from the year. Almost all student desires can be encapsulated in two words; Happiness and Learning. The Scandinavians have a single specific word Arbejdsglaede which literally translates as “happiness at work” (Zak, 2017:171). Happiness is a complex idea however for students it usually means; listened to/respected, enjoyment, safety, cared for/loved, and clear boundaries. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs purports that only when the physiological and psychological needs, including safety, are addressed can self-actualisation needs be considered. Only then will “a new discontent and restlessness… develop unless the individual is doing what he is fitted for” (Maslow 1943:383) which is achieving full potential through self-actualization. Ken Robinson calls this “finding your element” (Robinson 2009). In the classroom this is achieved by respecting students as capable; socially and academically – otherwise known as high-trust. Neuroscientist Paul Zak’s research (2007) shows that in high-trust cultures, people devote less time to monitoring others and are more likely to do self-actualising activities. Furthermore, he gives the life equation of “Joy = Purpose + Trust” (2017:171). We have previously established that students desire happiness – also known as joy – and they desire to learn – it is their purpose to “find their element” through learning experiences. The only aspect of the equation missing is trust! Zak goes on to summarise how leaders (teachers or otherwise) can foster a high-trust environment using the anagram OXYTOCIN. Here is a very brief summary using the anagram (in bold), simplified with modified elaboration for educators;

-

- Ovation: Celebrate growth and achievement

- Expectations: Maintain high expectations

- Yield & Transfer: Choice within parameters (agency)

- Openness, Caring, & Natural: personal authenticity

- Investment: personalise/differentiation, learning environment (expanded below)

One example of how this is made manifest in my classroom is through intrinsic motivation.

“Intrinsic motivation occurs when we act without any obvious external rewards. We simply enjoy an activity or see it as an opportunity to explore, learn, and actualise our potentials” (Coon 2010:332).

I trust that my students want to learn and therefore find transient “carrot and stick” inducements disrespectful.

A THREE DIMENSIONAL CURRICULUM

I believe that learning is best approached through a conceptual lens using various teaching methodologies, including guided inquiry, and tools such as visible thinking routines.

Lynn Erikson asserts that;

“The greater the amount of factual information, the greater the need to rise to a higher level of abstraction to organise and process that information.” (2007:2)

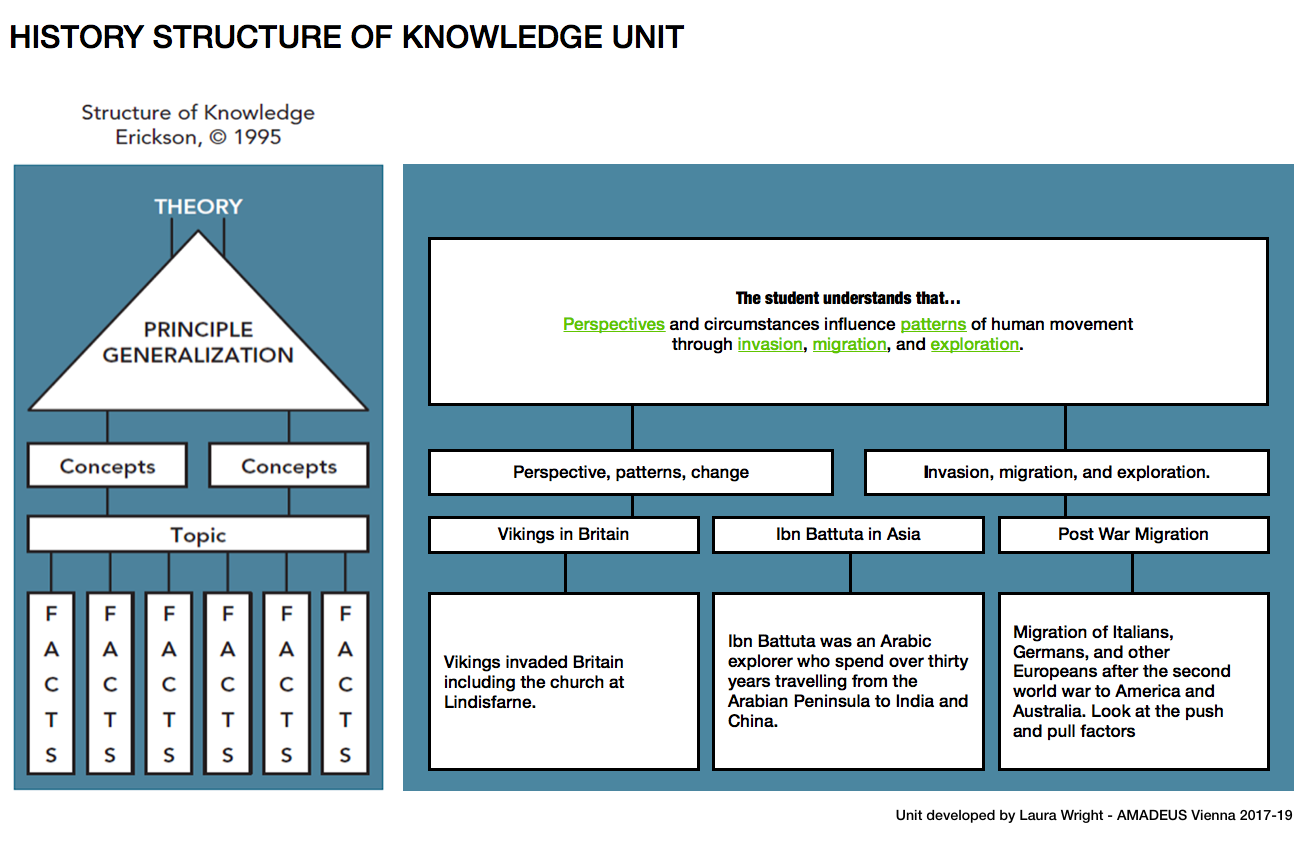

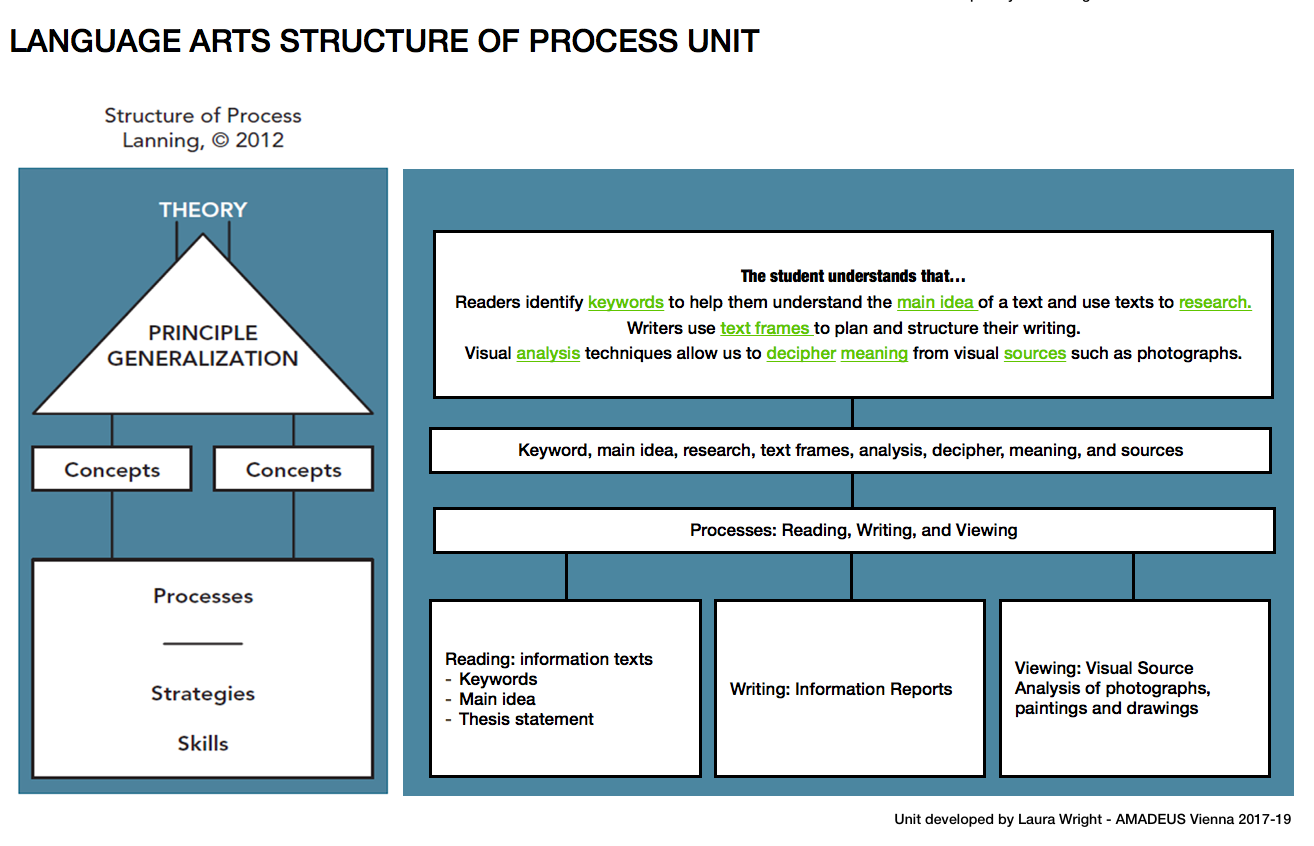

Thus there is an interplay between conceptual understanding and supporting facts and skills. This interplay or synergy between the lower and higher levels of thinking is central to the systematic development of intelligence. Furthermore, they have defined two structures of learning; the structure of knowledge and the structure of process. Both structures have concepts that support a principle/generalisation, which in turn inform a theory. All subjects have learning within these two structures. A sample transdisciplinary unit (using both structures to view the unit) that I created for my Grade 4/5 class (History, Language arts: Reading, Writing, and viewing) can be found in the appendix.

Within these frameworks, learning experiences can be anywhere on the Teaching Continuum: from structured to open. These include direct instruction, structure inquiry, guided inquiry, open inquiry, and discovery learning (Marschall & French 2018:8). In my teaching, I believe that each type of experience is important for learning. I use the guided inquiry cycle (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari. 2007), correlated with the IB Approaches to Learning, together with visible thinking routines from Harvard’s Project Zero. By combining all these ideas, learning becomes an active, relevant experience where students have agency and high standards of achievement are maintained.

THE PHYSICAL LEARNING SPACE

Finally, in the physical environment, I endeavour to create and maintain spaces that support and reflect these pedagogical values, especially through the use of documentation.

Tiziana Filippini, former pedagogista of the Diana School in Reggio Emilia, defines learning spaces as both container and content (Edwards, Gandini, & Forman, 1998). A learning space as container, “favours social interaction, exploration, and learning”. For example, interaction between students and with teachers can be facilitated by furniture layout. This could be desks where students are facing each other or a rug/cushions on the floor arranged in a circle; removing the teacher desk or having a workstation in an inconspicuous place in the room can also foster open communication. Simultaneous, a learning space as content: “containing educational messages and being charged with stimuli towards interactive experience and constructive learning”(1998). This I believe can be best seen in pedagogical documentation. Documentation is a connective process and product that can have a range of purposes based on different members of the community. For students, documentation can be the process of making thinking visible for clarification, reflection, refinement, and to build upon. For teachers, it can be for reflection (personal and collegial), planning, interpreting, and assessment. For the wider community, it can be a window to understand the learning taking place and a way for their voices to be added to the conversation. For all members, documentation brings together a community around the experience of learning.

Interesting research and work has been performed by Heidi Hayes Jacobs and the Fielding Nair Architectural Group regarding learning space design

To conclude, there are so many other aspects of my teaching philosophy that I have barely mentioned: literacy focus, parent integration, inquiry cycle, thinking routines, arts integration, the path to abstraction, Montessori, etc. The above points, however, give an outline of the principal characteristics of my teaching philosophy. Furthermore, the above points are ever growing and changing as I learn more through experience and professional development including reading.

Appendix

FOOTNOTE: In the Structure of Knowledge: facts about a topic are considered using the conceptual lens leading to a principle/generalisation, and informing a theory. In the Structure of Process: skills are combined to create strategies, which are then used in processes, that are considered using the conceptual lens leading to a principle/generalisation, and informing a theory.

References

Coon, Dennis., Mitterer, John O., Talbot, Shawn., Vanchella, Christine M. (2010) Introduction to psychology: gateways to mind and behaviour. Belmont, Calif. : Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Edwards, C. P., Gandini, L., & Forman, G. E. (1998) The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach–advanced reflections. Greenwich, Conn: Ablex Pub. Corp. [Kindle DX version]. Retrieved from Amazon.com

Erickson, H. L., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2007). Concept-based curriculum and instruction for the thinking classroom. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Corwin Press.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K., & Caspari, A. K. (2007). Guided inquiry: Learning in the 21st century. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited.

Malaguzzi, Loris. (1994). Your Image of the Child: Where Teaching Begins. Nebraska USA: Childcare information Exchange. Retrieved from reggioalliance.org/downloads/malaguzzi

Marschall, Carla; French, Rachel. (2018) Concept-Based Inquiry in Action: Strategies to Promote Transferable Understanding (Corwin Teaching Essentials) Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications.

Maslow, A.H., (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396. Retrieved from https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm

Rinaldi, Carlina. (1998). Projected Curriculum Constructed Through Documentation: Progettazione. In Edwards, C. P., Gandini, L., & Forman, G. E. The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach–advanced reflections. Greenwich, Conn: Ablex Pub. Corp. [Kindle DX version]. Retrieved from Amazon.com

Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2009). The Element: How finding your passion changes everything. New York: Penguin Group USA.

Robinson PhD, Ken., Aronica, Lou., (2015), Creative Schools: The Grassroots Revolution That’s Transforming Education. New York: Penguin.

Zak, P. J. (2017). The Trust Factor: The Science of Creating High-Performance Companies. New York: AMACOM. Retrieved from Questia School.